Questions?

Email us at: JandK@LivingGoldPress.com

HOME

HOME

|

Email us at: JandK@LivingGoldPress.com

|

Modoc War Photographer Louis HellerFrom the Studio to the Lava Beds and Back© Jill Livingston 2019 A version of this article originally appeared in the Friends of the Siskiyou County Museum Newsletter, Summer 2019 Photos from the Siskiyou County Museum Archives |

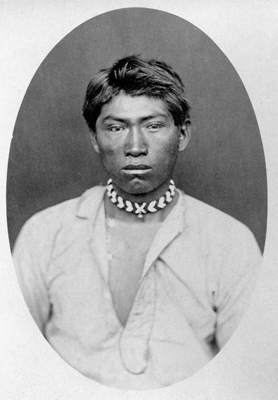

Hooker Jim, one of the most aggressive Modocs, as photographed by Heller after his capture. |

An Army encampment near Tule Lake as photographed by Louis Heller in 1873, one half of a stereoscopic pair. |

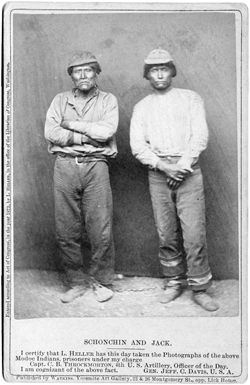

A carte de visite of Captain Jack and Schonchin in leg chains after their capture. |

|

When Louis Heller came out to the far northern California gold mining town of Yreka, Siskiyou County in 1864 to set up his photography studio he never imagined he would be cast in the role of “war photographer” a few years later. Heller was born in Germany, immigrated to the US and trained under a photographer in New York before he made his way west. California was a bustling place what with gold mining, developing agriculture and industry and growing cities. During this expansive period countless traveling photographers roamed the byways, taking photos in makeshift studios for transplants to send to the folks back home, and sometimes documenting the towns, countryside or natural wonders along the way.Heller set up his studio on Miner Street and began posing local families in the formal somewhat stiff style that was the norm, always striving to present his patrons as attractively as possible. Most popular were cartes de visite, or “calling card” photographs, 2.5” x 4” in size and mounted on cardboard. These could be presented to friends and family and were often mounted in albums designed just for them. In 1869 Heller sold the Yreka studio to his assistant, Jacob Hansen and moved to nearby Ft. Jones where he worked for the next 31 years. The majority of surviving portraits taken in north and western Siskiyou County during this era seem to be labeled either “Heller” or “Hansen.” But Heller wasn’t strictly confined to his gallery. In the summer he was an itinerate photographer, traveling a circuit around the county setting up temporary studios in small towns and mining camps to serve people who could not travel to his studio. When out and about he liked to photograph landscapes and mining operations and seemed to especially enjoy the rugged Salmon River area. In fact, the confirmed bachelor eventually (in 1889 at the age of 61) married Alice Daggett, sister of John Daggett, former California Lt. Governor and owner of Salmon River’s Black Bear Mine (subsequently - and still- the site of a famous “hippie” commune). Three years after Heller moved to Ft. Jones the Modoc War erupted in the Lava Beds area (now a National Monument) of eastern Siskiyou County. Although a day or two away on horseback, Yreka was something of a war “headquarters” by virtue of being both a trade center and the nearest place with a telegraph office. Thanks to newspaper reporters and the telegraph, the war was followed closely in newspapers and magazines all around the country. The fact that a small band of Modocs was able to hold off 1,000 army troops for several months during the winter of 1872-3 was a curiosity, and interest was piqued even more after “peace negotiations” resulted in an ambush where General Canby and one of the peace commissioners died. Heller set off for the battleground in late April, 1873 just after the Modoc band had been driven from the Stronghold where they’d spent the winter. He captured images of the Lava Beds area, including “Jack’s cave, Scarfaced Charley’s hole …and soldier’s camps” (as reported by the Yreka Journal). He also staged some battle scenes albeit using as Modoc stand-ins Warm Springs Indians hired as scouts by the Army. Although fighting was going on during the time of Heller’s visit, taking live action photographs of actual combat was virtually impossible at that time. Photography was then a cumbersome process that involved tents, heavy equipment and delicate glass plates. Set up was a long process and in a war situation would place the photographer in a precarious position as an easy target. So photographing only the “scene of the action” was not only just acceptable, it was praiseworthy in this era. Using a double lens camera, Heller came back with 24 stereoscopic views designed to be viewed in 3D using the popular stereoscope. A week after Heller went to the Lava Beds a photographer hired by the US government, San Francisco-based Eadweard Muybridge (famous for his photographic studies of animal movements) showed up. He took photos similar to Heller’s. Although he stayed only 8 days and never returned, Muybridge has received considerably more credit than Heller as a Modoc War photographer. Between the two of them, about 100 Modoc War photos are known to exist. By June 1st the last of the renegade Modocs had been captured. Once again Heller headed east. This time he photographed all of the captives and some of their families, turning the stunning images (somewhat ironically) into carte de visites that he sold through and later to the Watkins Yosemite Art Gallery, helping to ensure his obscurity. After the war was over Heller returned to his business of producing formal studio poses, including the larger format “cabinet cards,” 4.5” x 6.5” mounted photos that were the next trend. He also served as Justice of the Peace and later Postmaster of Ft. Jones, retiring to San Francisco in 1900, at which time he destroyed all of his glass negatives, as they “have no value.” |