Questions?

Email us at: JandK@LivingGoldPress.com

HOME

HOME

|

Email us at: JandK@LivingGoldPress.com

|

|

"Taking the Waters," |

|

Mineral springs, both hot and cold, are common throughout the west and have long been sought for their many healthful benefits and the simple pleasure of sitting in one. |

|

“Taking the waters” for physical or mental health was easy to do in early Siskiyou County, thanks to the many mineral springs located in the region. Maybe you sought relief from “ennui” (what we might call depression) or it might have been rheumatism (arthritis) that prompted your visit. Some springs were warm and just right for bathing; maybe there was warm mud to plaster on your face to tighten up the wrinkles; some springs were naturally effervescent and tasty; and some were not so pleasant to imbibe but were laden with minerals purported to cure a variety of diseases. But above all, the mineral springs were social gathering places.

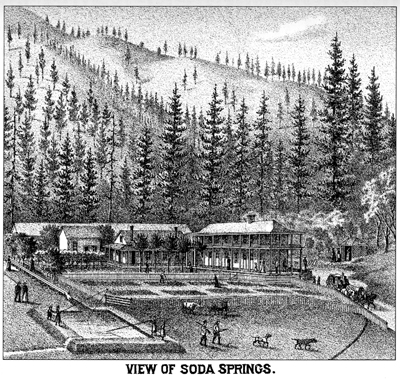

Most visitors to the earliest developed or semi developed mineral springs around the country lived close by or in the surrounding area. These 19th century “spas” were hubs of activity even before the Civil War when there really was no such thing as “tourism.” Here, what we think of as tourism did not flower until the railroad cut across the county in the late 1880s, bringing travelers from other parts of the state and country, and these were well-to-do travelers. In this time period all around the United States summer resorts - mineral spring spas, mountain retreats, beachside cottage communities - were built up by this genteel class of traveler. This was also when the western National Parks, with their large comfortable lodges built by the railroad emerged as vacation destinations.

It is interesting to note that the term “tourist,” as opposed to “traveler,” was originally a semi-contemptuous term that referred to the middle-class travelers that were beginning to show up around the turn of the 20th century. Obviously, the term has long since lost its sting. By the 1920s and 30s there was yet another development; automobiles loaded up for motor touring jammed the concrete roads, and tourism became thoroughly democratized.

|

South County Mineral Spring Resorts Lower Soda Springs and Castle Rock (north Shasta County) Yet business was brisk enough to warrant building hotels at both Upper and Lower Soda Springs. A man named George Washington Bailey, a former miner from Yreka and purportedly an invalid for four years, bought the Lower Soda Springs property, drank the water, regained his health and in 1858, built a modest inn at the stage stop. 24 years later, with railroad construction slowly working its way north, he sold out to the Pacific Improvement Company, the subsidiary of the Southern Pacific Railroad that established towns and built hotels all along its rail lines. In 1891 PIC constructed the considerably more upscale Tavern of the Crag. It had 250 rooms, a dining room that could seat 350 and “all of the most modern conveniences.” The three-story hotel burned after being struck by lightning just nine years later although other buildings, such as railroad baron Charles Crocker’s summer house, survived and it continued to operate haphazardly as a resort for the next three decades. Still called the Berry Estate after the San Francisco millionaire who purchased it in 1930 (there have been several owners since Berry), there is no public access, although the gazebo shielding the soda spring is visible when driving on Riverside Road.

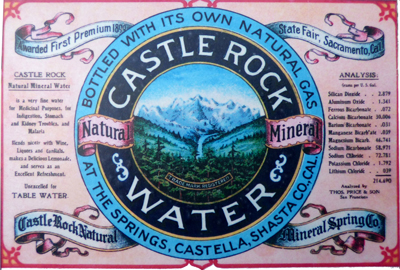

Soon after selling Lower Soda Springs, George Bailey built another mineral spring establishment a short distance south and this one you can still visit. Castle Rock Spring bubbles up in a rock cistern on the edge of the river within the Riverside Campground in Castle Crags State Park. The hotel was near the tracks on the opposite (west) side of the river so the springs were reached by footbridge. The Castle Rock Natural Springs Company started bottling the water that was “bottled with its own natural gas” and said to be good for indigestion, stomach and kidney problems, and malaria. In the 1930s the CCCs working in what had recently become Castle Crags State Park rebuilt the rock walls and steps in the mineral spring area and replaced the deteriorated footbridge.

|

|  |

|

Upper Soda Springs, Shasta Springs & Ney Springs By the time Upper Soda Springs closed it had already been eclipsed by picturesque Shasta Springs just up the road, a truly high-class operation and probably the most remembered local mineral springs establishment. Heavily promoted Shasta Springs was wholly a product of the arrival of the railroad. It opened in 1890. Trains delivered members of the “leisure class” laden with trunks and prepared to stay a couple of weeks or even the entire summer to the resort’s own elaborate train station. From there visitors took a 650-foot water powered tram or hiked the steep Zig Zag Trail through the forest to the large bench above the river where sat the lavish sprawling resort.

Even through passengers could disembark for a 20-minute stop to purchase souvenirs and fill small cups purchased for 15 cents with spring water from the trackside fountain. It was written that the water “bites the tongue with a most pleasurable sensation.” The layout included a bottling works but later entire train car loads of water were shipped to Sacramento for bottling. Shasta brand sodas, still a viable brand, originated right here in 1931; the first flavor was ginger ale.

Turn-of-the-century patrons of Shasta Springs took mineral baths (the water had to be heated) in the natorium, swim in a cold water pool or the river, visited Mossbrae and Hedge Creek Falls, hiked, fished, set up their easels outdoors to paint, played tennis or croquet, and of course, dressed for dinner. Later, visitors also arrived via Pacific Highway when it opened bringing a different class of traveler, and the allure of mineral spring resorts began to slowly fade. Shasta Springs was sold to the St. Germain Foundation in 1957 and is not open to the public.

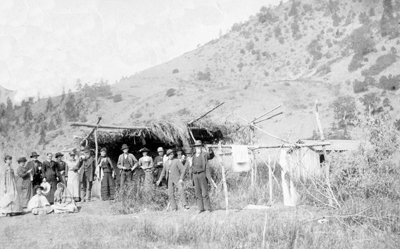

Heading north, Sisson (now Mt. Shasta city) was a base for mountaineering, hiking, botanizing and plein air painting. But for mineral water one headed a few miles west out of town to Ney Springs, or on arrival by train, took a two-mile carriage ride from the Cantara train station. A smell of sulfur announced your approach shortly before your arrival at the summer-only resort, with its 50-person hotel built by John Ney around the turn of the century. Two springs, each with different qualities fed the resort; Agua de Ney “cured” stomach and blood diseases, Beauty Water was “Nature’s Shampoo and Face Lotion.” Nearby 80-foot Faery Falls, a favored short hike for resort visitors, was pictured on the label of bottled Ney Springs water. Ney Springs was run by successive family members until it finally closed at the beginning of WWII. Today, a short hike up an old road will take you to the mossy remnants of Ney Springs resort. (A sulpjur spring on the Ney Springs resort site is pictured at the top of this page.)

|

|

North County Mineral Spring Resorts |

|  |

|

Klamath Hot Springs Around 1887 Josiah and Lile Edson bought the property and soon built a large hotel in a unique and spectacular style, especially for such a rural setting. French Second Empire Style was popular in that era. The building featured a flat mansard roof (allowing for a full third story) with numerous dormer windows. The building was faced in basalt (available close by) and had a first floor wraparound porch and second story balcony. But that wasn’t the only building. There was a bath house, a fish cleaning house, a concrete warm water swimming pool, an ice house, a smoke house, 6 guest cottages, barns, a blacksmith shop and an electrical plant. Besides the hot mineral water and mud baths there was world class salmon, steelhead and trout fishing in the Klamath River and Shovel Creek.

In 1911 the stage from the rail line was replaced by a seven passenger Locomobile (a pioneering automobile manufacturer in the pre-assembly line era), news that was reported even in the San Francisco Call newspaper. The hotel burned in 1915 but other buildings still stood including the guest cabins and ample camping grounds. A dance pavilion (still standing) was built with stones from the burned hotel and the party went on. Well known people such as Zane Grey and Herbert Hoover, both of whom were avid fisherman who frequented other sections of the Klamath and the Rogue River, signed the guest book.

The Klamath Hot Springs site is several miles out Copco Lake Road on the Topsy Grade stage road to Klamath Falls that branched off at of the California-Oregon stage road at Ager (where there is an E Clampus Vitus monument commemorating this). Be aware that the springs are on private property.

|

|  |

|

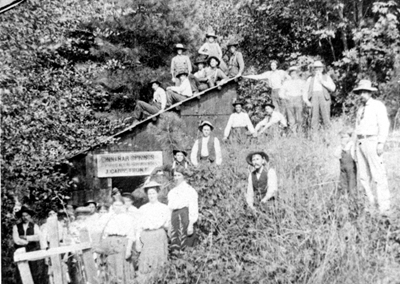

Cinnabar Springs and Colestin Mineral Springs By 1905 there was a good wagon road to the springs and a cinnabar mine nearby that employed 30 men. A dance pavilion was built attracting scores of revelers from the mines and residents from down on the river on a Saturday night. During Prohibition there was a conveniently located still. By the 1930s Cinnabar Springs was on its last legs. Today you can drive up a forest road to the site but it is difficult to figure just where it was and harder to imagine the vibrant scene in this out of the way place 100 years ago.

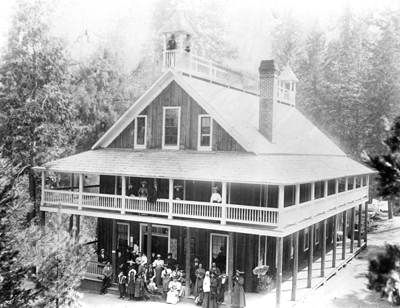

The second Siskiyou Mountain mineral spring resort was Colestin just over the border in Oregon, another case of sitting right beside the stage road and later, right on the tracks with its own train stop. Brothers Rufus and Byron Cole ran the still standing (as a private residence) stage stop, Cole’s Station on the California side in the Hilt Valley. Byron saw an opportunity in 1881, with the railroad surveyed and in the works, to build the Colestin Mineral Springs Resort on the stage road further north up the mountain.

Colestin was another resort heavily publicized by the Southern Pacific Railroad in their Sunset magazine and assorted pamphlets and postcards. Byron built a large two story hotel out of surrounding timber and furnished it with elegant furniture shipped from the east. Aside from the bathing in and consuming of mineral water, there were the usual genteel activities of croquet and tennis. But there were also nightly campfires and ample camping grounds. Camping in those days featured commodious wall tents and sundry equipment to mimic the comforts of home.

By the mid to late 1920s and the Cole’s long gone, Colestin was no longer being run as a resort although the old hotel stood tall by the tracks until sometime in the 1980s. The new owners, three Greek brothers, George, Gus and Theo Avgeris, bought up 3,000 acres in the area, logged, mined and ran cattle and goats, made cheese. In 1931 they built a bottling plant and began to sell bottled Colestin Water around the country. In 1943 they were taken to court for “mislabeling” due to the extravagant medicinal claims printed on the bottle labels. Perhaps by that time people were put off by such hyperbolic unprovable claims.

Curative assertions aside, I think many of us still treasure a hot water soak, and if it is in a natural mineral spring, so much the better.

|

|

Some sources used for this article: Dunsmuir by Deborah Harton and Ron McCloud, Mount Shasta by Darla Mazariegos, Shasta’s Headwaters by Craig Ballenger, Historical Landscape Overview of the Upper Klamath River Canyon by Stephen Beckham, assorted issues of Siskiyou Pioneer and Table Rock Sentinel, “Tourism in America Before World War II” by Thomas Weiss in Journal of Economic History , Vol. 64 No. 2. |